In January 1945, Chuykov's 8th Army forced the Vistula River, suffering heavy losses. (Remember the song "On the Fields Beyond the Sleepy Vistula"?) Due to the heavy losses, our 5th Army under the command of General-Lieutenant3 Berzarin was ordered to move forward and take the 8th Army's place. This was right where the Pelitsa River empties into the Vistula, at the mouth of the Pelitsa.

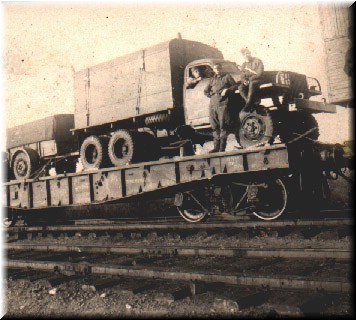

SCR-399 tactical radio station, hauled by Studebaker truck. Photo courtesy of Serge Matveyev.

At five o'clock, the 5th Army took up the position of the 8th Army, which withdrew to the rear. The day before, the 8th Army had forced the river, but did not advance. On our side of the river was Poland, on the opposite side Germany. At this point there's a pretty good bend in the Vistula. The difference between Poland and Germany was striking. On our side, a bumpy, muddy country road, similar to ours at home, and on the other side a first-class concrete highway descending to the river right across from the Polish road. On our side were ramshackle, dirty huts, into which an incredible number of Polish peasants were crammed. Other the other side were tidy, standardized German cottages made of silicate brick. There was ice on the river.

The Germans had not yet recovered from the attack to understand the situation following the blow struck by the 8th Army, and had not redeployed their reserves properly all along the line to cope with it. Many of their units withdrew hurriedly to the Oder in order to man the last line of defense before Berlin. Toward evening I arrived on foot at our battalion command post since Colonel Shestatskiy, a very good person, had arrived there by vehicle; getting ahead of myself in the story, I'll say that he perished after the forcing of the Oder, during the liberation of a concentration camp in which our prisoners were held. After the gates of the camp were thrown open, a crowd of prisoners poured out to greet their liberators and didn't notice in the crowd an SS guard who had changed into a prisoner's uniform and who shot the colonel at point-blank range with an automatic weapon. In Dubossary, Moldavia, there is a street named after Shestatskiy. Also at the battalion command post at that moment was my good friend, Senior Sergeant Fedya Glushko, the division radio operator, who before the war served in the Pacific Fleet, and before entering the military was a bookkeeper in the "Khabarzoloto" Trust4, and Captain Cherednichenko, the Communications Chief of the same 288th Infantry Regiment in which I served.

No order to attack had been received, but such an order was literally floating in the air. Since the situation was unclear and it was rapidly getting dark, the majority of officers decided to spend the night at the battalion command post. I stayed with them, and had an RBM5 radio with me.

There were about twenty people in a room of the battalion bunker; we slept on the floor, on the table, and under the table. As it would quickly become clear, the position under the table had its advantages, and that's where Fedya Glushko was. I was woken up by a loud commander's scream; people jumped up and a powerful flashlight threw a beam of light. There was no gunfire, though in such situations one expects a burst from an automatic weapon or an explosion from a grenade.

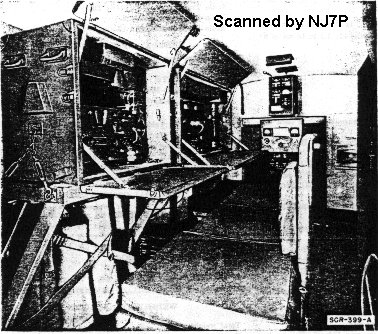

There were many people in the room; someone hurriedly lit a wicker lantern. Top brass!!! It turned out that Captain Cherdnichenko and I were pressed against the wall, where our communication equipment was located; we, like everyone else, stood at attention. In the reflected light of the flashlight pointed at us, I saw a stocky man in a long leather waterproof coat. I should point out that these coats were delivered together with powerful American SCR-399 radios installed in "Studebaker" automobiles with generator trailers; the coats were intended for the drivers of the Studebakers. However, as a rule, the coats were quickly removed by front-line or even by rear-area supply personnel and transferred not even to middle-ranking but only to senior officers since there weren't many of the radios (or coats). To my horror, I recognized the owner of the American coat as Marshal Zhukov, the front commander. Zhukov was very irritated, not to say furious, at our lack of readiness and at our sleepy state. Later I learned that that night he was traveling around the forward area in the automobile and was spotted by German reconnaissance, which showered his group with mortar shells. The automobile and communication equipment were put out of commission and the Marshal himself, with whom the staff of the front had temporarily lost contact, was obliged to make his way on foot with his group and guards to the location of the nearest unit, which turned out to be ours...

In addition to a Studebaker truck, the SCR-399 was equipped with many pieces of equipment, including a Hallicrafters BC-610, and a coveted long leather waterproof coat! Picture courtesy of Bill Beach, NJ7P.

He listened to Shestatskiy's report nonchalantly and impatiently, turned away from him, and came right up to Cherednichenko and me. He was fiddling with a cavalry stock, a short walking stick with a small leather strap on the end for encouraging a horse. "Why aren't you attacking?" he asked slowly with a threat in his voice, as though addressing everyone. In reply there was stony silence. Turning to our group, in which the nearest to him happened to be Captain Cherednichenko, he asked, even more threateningly, "communication, where's your communication?" The captain tried to mumble something to the marshal, but was stopped by a blow of the stick to his face. "Provide communication!" he hissed, threatening a little with the stick a second time, now toward me. I stood glassy-eyed at attention, like a statue, as I was well acquainted with front-line stories about the legendary ferocity of the marshal, who could, in a fit of temper, shoot someone for disobedience or looting. Letting out even two peeps in reply to Zhukov was a hopeless case for me6.

Apparently Zhukov correctly judged the state of mind of the young soldier7 and turned to talk with others. Right away one of his colonels, a communicator, ran up to us. He forced us out of our stupor. "Boys, give the marshal everything you've got." I switched on the RBM and connected and tuned the antenna. I must have done everything like a whiz, in a few seconds. Since I didn't know either the frequencies or the codes of the front staff, the colonel took my place at the operating position.

Boy, that was DX! I'll probably never hear such a pile-up8 again. After the first code phrases were spoken into the microphone, the quiet frequency literally exploded with hundreds of stations. The general headquarters had found the missing front commander. Quickly automobiles arrived, and the unexpected delegation departed. Cherednichenko applied iodine to the wound on his face, and Fedor Glushko was the happiest of all -- the whole time he hadn't crawled out from under the table and hadn't been noticed by anybody. He simply couldn't physically get out after all those who were sleeping stood up!

Translator's Notes:

1. This article throws light on the character of Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgiy Konstantinovich Zhukov, four-times Hero of the Soviet Union, who is still revered in Russia for his role as a military leader during World War II. An organization devoted to his memory existed as of 1995, when his daughter was interviewed for an article, "Savior of the Fatherland," published on the occasion of the 120th anniversary of his birth.

2. U1LP is a special callsign assigned to radio amateurs who are veterans of the "Great Patriotic War" -- the two periods of World War II during which the USSR was at war with Germany and Japan. The author of the article, Vladen Borisovich Gorbulev, emigrated to Israel, where he was assigned the amateur radio callsign 4Z5BP. He and his wife Lyuba failed to adjust to life abroad, returned to Russia, and are now living at 188917, Leningradskaya oblast', Vyborgskiy rayon, poselok Glebuchevo, ulitsa Mira, d.8, kv.5 (8 Mir Street, Apt. 5, 188917 Glebuchevo Settlement, Vyborgskiy Rayon, Leningradskaya Oblast').

3. A general-lieutenant is a two-star general, equivalent to a U.S. Major General.

4. Khabarzoloto was a gold trust (zoloto = gold) in Khabarovskiy Kray, a vast territory in the Soviet Far East (beyond Siberia). Extensive gold mining took place in this area, largely performed by prisoners in labor camps run by the GULAG (Main Administration of Corrective Labor Camps) of the NKVD.

5. RBM = Battalion Radio, Modernized.

6. Translator's note: This could mean that Cherednichenko feared Zhukov would strike him or shoot him if he said anything, or that, given his state of mind, Cherednichenko found it impossible to speak. It could well mean both.

7. Translator's note: I assume the author is referring to himself here. He was clearly, and with good reason, terrified of Zhukov. Zhukov apparently sensed this and moved on.

8. "DX" and "pile-up" are slang terms used by radio amateurs to describe the chaos created when a mass of stations, often interfering with one another, vie to communicate with a single desired station, in this case with the battalion station that was temporarily serving as the front commander's station.

HOT LINKS:

Home

|

Search QTH.NET Lists

|

Blast from the Past

|

Photo Archive

|

For Sale/Swap

Click here

to contact webmaster.

Click here

if there is no left-side menu frame.

This page last updated 30 Nov 2024