|

S-19R Restoration

Project Doug Moore, KB9TMY |

|

S-19R Restoration

Project Doug Moore, KB9TMY |

Restoration

Notes – Hallicrafters S19R

August 11, 2000

Bottom of Chassis After Initial Cleaning, Before Rebuild |

As received, the receiver

appeared to have all the parts. The bandspread bezel and

"glass" were loose, the two tube shields were

loose inside the case, and the overall case and chassis

were very dirty. Upon inspection of the under chassis, I found a kludge capacitor in parallel with the first section of the twistlock electrolytic, and there were quite a few spider webs. There were also lots of old paper capacitors, probably leaky, old style body/end/dot resistors, and a piano tuning felt wedge jammed in the BFO coil. Neither of the tuning dials worked due to the age of the dial cord, which though intact, was stiff and brittle. Since there is no removable panel, it appears the complete tuning assembly must be removed to restring the dial. No attempt was made to apply power. It is a certainty that the twistlock can is bad, so this will have to be rebuilt or replaced. Not sure yet how to approach cleaning up this beast – maybe remove the tubes and tuning assembly, and start from there? The tuning capacitors, shafts and dial plates will need cleaning, and it will need new dial cords. |

To start, the kludged add-on

capacitor was removed, and most of the spider webs cleaned out. A

schematic was available on the BAMA website. This schematic was

nearly the same as my unit except for the tube complement. On my

receiver, a 6K7 and a 6Q7 are used instead of the 6SK7 and 6SQ7

shown in the 19R. I have since discovered there were two runs of

S-19R, and mine is the earlier run. I figured a logical place to

start would be with the dial cords. Since the whole assembly was

quite dirty, and had obviously had several "quickie"

fixes applied, (like tape around the shaft) it looked easiest to

remove the whole works. This is accomplished by unsoldering two

wires from the tuning capacitor on the bottom of the chassis, one

ground braid on the top side, then removing the main dial, knobs

and the mounting nuts holding the tuning assembly. Two of the

mounting studs have ground lugs attached. These have two nuts,

one holding the tuning assembly, and one holding the lug. (Remember

this when you re-assemble.) Once this is all loose, you need to

loosen the setscrew on the bandspread dial and push it back

slightly on the shaft, so it will clear the top of the case. The

entire tuning mechanism can then be removed and serviced.

Once out of the chassis, I made a sketch of the dial cord

stringing, such as it was. The old cord was removed, and the

tuning assembly frame was stripped down to bare metal by removing

the shafts and tuning capacitor. This frame was scrubbed with

kitchen cleanser, rinsed and given a light coat of deoxit. The

shafts were cleaned and polished, then trued up slightly. The

tuning capacitor was sprayed with WD-40, scrubbed carefully with

a brush, then rinsed and blown out with an air hose. A bit of

deoxit was sprayed on the rotor wipers, and a drop of silicone

grease was applied to the two bearings. The tuning shafts were

then re-installed in the metal bracket, using a small amount of

silicone grease in the bearings. The shorter, single diameter

shaft goes in the top bracket, and the other two (which are

identical) go in the bottom. The tuning capacitor was remounted

and checked to insure its shaft was parallel with all the other

shafts.

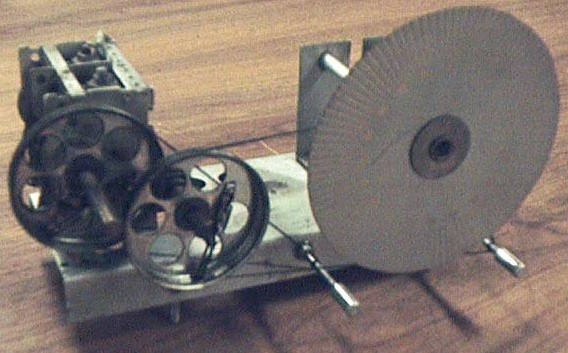

Tuning Assembly After Rebuild and Restringing.

Next job was the

restringing. For the cord I used my standard 45lb Dacron fishing

line. I started with the main tuning, since it is strung behind

the bandspread cord. Initially, I strung it exactly like the

original, with both ends of the cord tied to the spring. After

trying it out this way, I felt there was not quite enough

tension, because one end wraps a full turn around the tuning

capacitor pulley, while the other end only goes about a quarter

turn around the pulley. The spring cannot take up the slack on

the short end of the cord because of the friction of the long end

around the pulley. So, I undid the thing, and re-strung it

starting with a tied loop attached to the spring lug on the

pulley, wrapping around the pulley one and a half turns, then

around the tuning shaft two turns, then back to the tuning

condenser pulley, through the hole in the pulley then tied to the

spring with as little slack as possible. After gluing the knot,

the other end of the spring was attached to the spring lug, and

the whole thing worked much better.

The bandspread cord was done in a similar manner. I was a little

surprised that the cord in the original stringing did not do a

complete wrap around the pulley on the bandspread dial. I tried

stringing it with a full wrap but it seemed cumbersome and I wasn’t

sure I could move the dial back far enough to get the assembly

back in the cabinet. So, I stuck with the original stringing,

except for using a tied loop to the spring lug on the long end.

This appeared to be the way Hallicrafters did it originally, and

if it worked for them it should work for me. I figured the worst

that could happen would be that the bandspread dial could slip,

but it could be easily corrected by opening the top of the case

and turning it slightly. On this receiver, the bandspread dial is

not marked in frequency, but with just a 0-100 logging scale.

The tuning assembly was now ready to reinstall in the main

chassis, but first I needed to do some cleanup. I removed the

remaining knobs, and the old twistlock can. Due to the fading of

the old wire colors, and my own partial color blindness, (I can’t

tell a 100 ohm resistor from a 1meg without an ohmmeter.) I

marked the removed wires with stick-on numbers, and made notes as

to which section of the capacitor was connected to which number

wire. I started the cleaning with a mild dishwashing soap and

water, scrubbing the chassis with a brush and being careful not

to get any water near the speaker, transformer or IF cans. There

was a lot of "gook" around the area where the old

twistlock had been mounted; indicating it had been leaking for

some time. This stuff required a little more aggressive cleaner

to remove, but Ajax seemed to work. The corroded spots on the top

of the chassis and on one side of the chassis now became very

visible. The front panel, however, looked reasonably good. I

decided to address the cosmetic issues as needed during the re-assembly

phase. After drying the chassis, I had a close look at the

speaker. The cone looked quite dry and brittle, and I made the

mistake of touching it, only to have my finger go right through.

Oh well, live and learn. Time to remove the speaker and have it

reconed. The speaker is held to the panel by four ornamental

screws, rubber grommets and nuts. Six wires pass from the speaker

and output transformer through the chassis. These were marked as

described above, and then the entire speaker assembly was removed.

All rubber grommets were either turned to goo or brittle.

Fortunately, these are still readily available. I saved samples

of the sizes I needed and tossed the rest.

Top of Chassis After Removal of Tuning Assembly and Initial

Cleaning

Next I installed the new

twistlock, and decided to replace all the old paper and wax

capacitors. Most of these were no problem, with the exception of

C4 and C5. One end of C4 connects to a terminal on the front deck

of the bandswitch, which was virtually inaccessible. The wiring

is tight here and it did not appear feasible to remove or rotate

the bandswitch. I elected to cut the bandswitch lead close to the

capacitor, strip off a bit of the sleeving, slip on a piece of

heatshrink tubing, then splice and solder the lead from the new

capacitor to the stub. After this, the heatshrink was slipped

over the splice, and a bit of heat applied. One end of C5 goes to

a very crowded ground lug, the same one that carries a ground

braid through the chassis to the tuning capacitor. Even the

original assemblers couldn’t get all the leads through the

hole in this lug, but the real problem is the other end of C5,

which goes to the bottom terminal of an antenna coil. Again, this

connection is nearly inaccessible. Though this capacitor could be

relocated, it’s placement made sense RF wise, and I didn’t

want to second-guess the original designers. After some study I

elected to temporarily remove one wire from the adjacent coil.

This allows access to the lower coil terminal, providing you have

a small pencil-tip iron. Capacitor C22, which goes from one side

of the AC line to the chassis, was replaced with a capacitor

certified by UL/CSA for this type of service. A one lug terminal

strip was mounted using one of the transformer mounting screws so

that a fuse could be added in series with the hot lead from the

line cord. The old line cord was replaced with a somewhat more

rugged polarized cord. I checked the values of the old dog bone

resistors, and amazingly, didn’t find any that were off by

more than 20%, so I left them alone.

While the speaker was out for reconing, I did some touch up

painting on the chassis and side panels using flat black Krylon

spray. The front panel looked pretty good after a light rubdown

with WD 40. There were some white paint specs here and there,

which I touched up by spraying some Krylon on a Q-tip and dabbing

it on. (Someone once said since these spots are so common on old

radios, people must have used them in place of a tarp when

painting.) I cut out a new bandspread "glass" from thin

plastic, and scribed a line down the center. I tried inking this

line, but decided I liked the scribe better. I then installed new

grommets in the tuning assembly holes, loosened the setscrew on

the bandspread dial and moved it back a bit, then remounted the

tuning assembly and reconnected the wires. Be sure to use plenty

of heat on the shield braid connection, and don’t forget the

solder lugs that go on two of the mounting studs. After the

tuning assembly is mounted, move the bandspread dial forward and

tighten the setscrew. NOTE: Failure to move the bandspread dial

back during tuning assembly removal and re-installation may

result in cracking the plastic dial. Also, beware of the screw

head holding the bandspread bezel, it can scratch the dial.

Front Panel After Initial Cleaning (Note White Paint Spots).

The headphone jack is intended for high impedance headphones, being fed by C15 from the output tube plate. If you want to use low impedance phones, you will have to install a new headphone jack with an isolated SPDT switch, and do some rewiring. This is best done when you are reinstalling the speaker, as some connections between the output transformer and the speaker have to be rearranged.

|

When the speaker arrived, I installed new grommets, mounted it back in the case, and reconnected all the wires. The knobs were cleaned up and reinstalled. A bit of white crayon restored the white dots on the audio gain and BFO pitch knobs. I used Naval Jelly and fine steel wool on the main dial, with results that were fair. (Rock Sea is supposed to be working on a new dial for the S-19.) The plastic pointer and spacer washers for the main dial were reinstalled. The tubes were unwrapped and tested. Only the rectifier, (an 80) was reinstalled for now. |

The receiver was plugged

into a variac and the B+ voltage monitored. The variac was turned

up to the point where the rectifier became hot enough to do its

stuff. Everything was carefully watched for signs of

spitzensparken and fusenblowen. So far, so good. With 70 volts AC

from the variac, the B+ read about 130V. With 120V input, the B+

was reading almost 300V. The rest of the tubes were then plugged

in, at which point I noted I had a metal 6K8 instead of a glass

one. The converter tube shield was therefore not required, which

is why it was loose when I first inspected the receiver. The

shield IS required for the 6K7 IF amplifier.

I was now ready for the first test. I turned the radio on with

the variac set to 100V. After the set warmed up with still no

smoke, I turned up the volume and touched a pencil to the top of

the audio gain control. Some hum was heard, indicating the

amplifier and speaker were working. I then switched to Band 1,

jumpered A2 and GND on the antenna terminal strip, and connected

about a 10ft. piece of wire to A1. On tuning, several AM stations

were heard and the sound quality was pretty good. Turning on the

BFO switch, I was able to adjust for zero beat with no problem.

Under these conditions, with the variac turned up to 120V, the B+

from the rectifier read 255V. No specific voltage is called out

on the schematics I had, but the output of the optional vibrator

supply was shown as 260V, so I figured I was close. I played the

radio all day at 120V and all seemed to be in order. The

transformer laminations read 58 degrees C after 7 hours. A bit on

the warm side, but not what I would consider hot. It’s a

personal decision whether to run this receiver through a voltage

reducer, setting the input voltage at 110V, which was probably

its design center.

While "burning in" the radio, I cleaned, straightened

and repainted the top and bottom cover panels. The "feet"

on the bottom were replaced after the paint dried. Apparently,

there was some kind of paper legend once attached to the bottom,

which may have identified the trimmers, but this was missing on

my particular set. It may be that the purpose of this was more to

cover the access holes than inform, I really don’t know. The

trimmer information is included in the schematic and alignment

instructions anyway.

Satisfied that nothing was going to burn up, I proceeded to align

the set according to the instructions. This set uses "padder"

capacitors to adjust the low end tracking on bands one and two,

rather than adjustable inductors as used on later radios. High

end tracking is set by trimmers as usual. There are no padders

for bands three and four, so low end tracking is set by design,

and hopefully will be pretty close. During alignment, keep the

signal generator output as low as possible, and set the

bandspread at MINIMUM capacitance. Mine tuned right up with

little difficulty, although the tracking on band four was not

perfect. I adjusted trimmer CH for best compromise around the 10

meter area. The final alignment should be done with the bottom

cover in place, as it influences the inductors.

After alignment, the performance of the radio was surprising,

considering this model was made about 1938, and had all but one

of the original tubes. Buttoning it up, I took it upstairs and

hooked it to the attic dipole. The performance on bands 1 and 2

was just about the same as my SX-117, though not with as much

selectivity. It was possible to copy sideband on 75 meters with

good intelligibility. Tuning sideband with just a BFO is a bit

tricky, but not impossible. Performance on band 3 was definitely

poorer than the 117, but still not too shabby. Performance on

band 4 was slightly better than poor. It could be that a new 6K8

would help, but since this receiver is to be used mainly for SWL,

I wasn’t too concerned. To me, it was amazing that it did as

well as it did for a 1938 radio with no RF stage. The finished

product didn’t look like it just came out of the box, but it

sure looked a lot better than it did when I started, and was

quite presentable. The weak spot is the main dial. If a

replacement scale becomes available, I’ll probably buy it.

|

It is my hope that these notes assist you in your restoration of a similar receiver. There is a lot of history in these early receivers. Who knows what sounds came out of its speaker? The celebrations on VE day? Truman’s speech when he fired General McArthur? Cold war propaganda from Radio Moscow? I know I’ll think about this every time I play this old Hallicrafters. |

Doug Moore - KB9TMY (formerly K6HWY)

This page last updated 16 Mar 2002.